When brands use third party controlled intellectual property rights in their campaigns, usage is one of the key cost drivers. This applies to music, on-screen talent, photography, stock images and clips, indeed any IP controlled by 3rd parties. Remember that you are essentially renting someone else’s equity and the usage defined in the licence determines how you can exploit that equity.

When brands use third party controlled intellectual property rights in their campaigns, usage is one of the key cost drivers. This applies to music, on-screen talent, photography, stock images and clips, indeed any IP controlled by 3rd parties. Remember that you are essentially renting someone else’s equity and the usage defined in the licence determines how you can exploit that equity.

The three key elements of usage are:

- Term: How the long the campaign will run

- Territory: The markets in which the campaign will run

- Media: The channels on which the campaign will run

(i) Term

Historically, UK advertising campaign Terms were typically one year. Whilst music rights owners don’t have set rate cards, they’d have a sense of the sync licence fee that a particular song or recording could command in their market for that period. Of course, they’d want brands to license for a full year rather than shorter periods and so would make short Terms disproportionately poor value. Here’s a typical example:

In fact, some music rights owners may refuse to grant you a one or three month licence, especially for a famous music title. They want the big fees for the full year term.

Of course, media is now bought in fragmented bursts, especially for broadcast media. Your media agency might devise a plan which could be described as:

- Six non-consecutive four week bursts within a twelve month window

What does this mean to the licensee and licensor?

The brand (licensee) thinks:

“I’m only buying twenty-four weeks of media, which isn’t even six months, so I expect a lower fee”.

The music rights owner (licensor) thinks:

“This is essentially a full year licence – I don’t care whether or not the campaign is on air the whole time – we’ll charge them for a full year”.

What’s the take-out for marketers?

The music rights owners know they’re unlikely to license the track you want to another brand in the gaps between your bursts. So there’s no reason to grant a discount on what would have been the full year’s fee. Yes, this seems unreasonable and quite contrary to how media is bought on your behalf by media agencies. However, the music industry is of a different mindset. They just think about the total length of the licence term, not the weight of media or how many people get to see your campaign.

Music rights owners’ perspective is that their title is tied up with your brand from the start of the first burst to the end of the last burst, irrespective of the breaks in between.

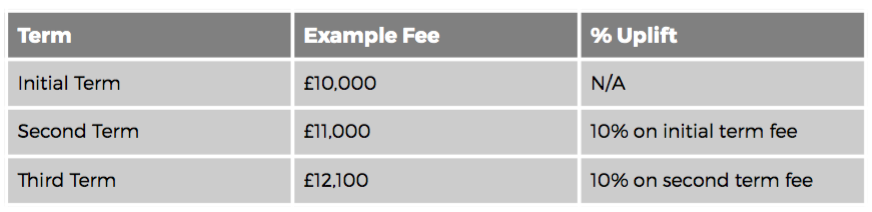

Let’s now consider why the Term line on the graph is curved. This relates to options which we’ll examine in more detail in Section Three, Chapter 13. For now, remember that if you include an option to extend the Term by the same period again, it’s usually possible to limit any fee increase to 10% above that which you paid in the initial term – provided that you exercise the option before the term expires. Here’s how it works:

You might think that you deserve a discount as a repeat customer if you extend the licence. In any other industry you might be right… but that’s not how the music business works. what you should know is that if you don’t include options in your original deal, the fee escalation for successive terms will be far greater than 10%. In other words, you are in a better position to negotiate what you might like to happen in the future while you are brokering the initial deal. Any bargaining power you may have will effectively be reduced to zero after the fact and you will certainly pay more.

(ii) Territory

Just as a reminder, when brands speak about “markets”, music rights owners speak about “territories”. So in any sync licence, the territory section lists the countries or markets in which the campaign is intended to run.

As you might expect, the more markets, the higher the fee. In the usage graph at the start of this chapter you can see this clearly with a steep line from uK only on the left, to world on the right.

As a marketer, there are a few issues you need to understand about Territory:

(a) Bulk Buying vs. Targeted Buying

It’s a common problem in decentralised businesses that the global marketing team doesn’t have complete control over the local market teams. So the former doesn’t know in advance what the latter needs. They simply can’t predict which local markets will run the campaign until it’s been produced and possibly tested locally.

When buying third-party IP rights, the “sledgehammer to crack a nut” solution is simply to buy a global licence. This will of course command a premium fee and could turn out to be very wasteful if only a handful of markets run the campaign.

Alternatively, the more cautious approach is to buy only the markets you need now, and negotiate options for all the others which have even the slightest chance of running the campaign. you must secure those options in advance to avoid excessive fee inflation arising from future re-negotiation. In contrast, the music rights owners will resist the grant of options. They may say, “let’s deal with that when the time comes,” which should sound the alarm bells to keep negotiating. That said, if you subsequently exercise many options and end up buying most of the world piecemeal, you’ll end up paying more than had you bought a global licence from the outset.

It’s a tough call, but you need a clear perspective on which markets you need now and which ones you may need in future.

(b) “Don’t See, Don’t Care”

When brokering licences for US controlled music titles, or titles written or recorded by American talent, be aware of their perspective on “Domestic” versus “Foreign” markets.

For managers of US talent, America is the world and everywhere else is less significant. Yes, that’s a bit harsh, but it’s not so far from the truth in many cases. This is even more true when the talent is very successful in the States. If you can exclude the US from your campaign, it will dramatically lower the licence fees. Whilst artists and their managers will really care whether or not their domestic audience can see a campaign, they’re less concerned if it’s invisible on their home turf.

For example, American actors sometimes appear in Japanese commercials, which no US consumer ever sees. The talent is happy to take the large fee, but the fans at home aren’t aware of the TV spot. This concept is wonderfully demonstrated in the movie Lost In Translation, where Bob Harris (played by Bill Murray) features in the “Suntory Time!” campaign for Suntory whisky. To some degree, this perspective is also true for music artists. Of course this has huge implications for online campaigns.

(c) “They’re famous here. So they’re expensive everywhere”

Perhaps contrary to (b) above is a US perspective which doesn’t acknowledge that huge domestic success might not translate in foreign markets. I’ve worked on campaigns where our client wanted to license a track by an American artist who was very successful at home but unknown in Europe.

Naturally the US option fees were very high, but so too were the European market fees. The artist’s US label and management didn’t care that the artist was unknown in Europe, their approach to global pricing was driven solely by a US perspective.

(iii) Media

I’ve included the graph here again to demonstrate music rights owners’ approach to pricing Media.

This wasn’t set in stone, but the general trend was that TV attracted the top fees, Cinema was cheaper, with Radio cheaper still. Any other non-ATl usage was often referred to a “non-theatric” or “industrial” and considered to be less valuable to rights owners as the potential audience was smaller.

Of course the internet changed everything and online media was initially bundled into ATl campaigns with little impact on cost, particularly during the second half of the noughties. It was accepted that all online use would be global even if the ATl campaign was limited to local markets.

As a marketer, you need to be aware that this has all changed. From 2013 onwards, we’ve seen major music rights owners, especially music publishers, take a very aggressive stance on online pricing. It’s no longer just bundled into ATl campaigns but is seen as a channel equally as valuable. This reflects how brands use online, especially those targeted at a young demographic who often shun TV in favour of YouTube. No longer can you think “it’s just online, so the music will be cheap”. If it’s on YouTube, many music rights owners will consider that almost as valuable as bought broadcast TV media.

(iv) Context

(a) Content vs. Media

It’s imperative to clearly list all the pieces of video content onto which you want to dub the music. If it’s an ATl spot, there will probably be a broadcast version which will also run online. However, there may also be various other online-only videos which might include “behind the scenes”, “the making of”, “film of the film”, “interviews”, “out- takes” plus a long form version of the spot for in-store usage.

These may contain elements of the main ATl spot but will probably also include additional footage. In the licence request you need to clearly list:

- Each content piece

- The media / channels in which that particular piece will be used

Don’t just lump “behind the scenes”, “the making of” into your media list for the ATl spot. They are not media channels but separate content pieces, hence the need to create a clear list so rights owners can see which piece of content is to be used in which media.

(b) Overt vs. Subtle Branding

Many marketers misunderstand how music rights owners think about the “context of use”, especially for online video. It’s important to be completely transparent about your intentions.

If the online video is overtly branded and product-led, it will appear to music rights owners as if it’s a commercial. The fact that it’s for online use only and not in ATl bought TV media is less significant – it’s a piece of advertising and the licence fees charged will reflect that.

In contrast, if your online video is mostly educational, music rights owners will price it differently. Let’s say your brand is a supermarket retailer. You might have a strand of your YouTube channel devoted to cooking and recipes. The products you sell might be subtly visible in the video, but essentially it’s a “how to cook this dish” video. Music publishers and record labels won’t view this as overt advertising and will be more lenient on licence fees. In contrast, the online usage of your blockbuster Christmas TV spot will be treated differently.

Remember that context of use is an important cost driver. You must be transparent about your intentions and disclose the full script of each film as part of the licence request. Sometimes rights owners may even ask to see the storyboard.

(v) “Buy-out”

This is a particular bug-bear of mine. Brands and agencies frequently use the term “buy- out” which suggests that they’ve bought out all rights in a particular piece of third-party IP. This often leads to the false assumption that the brand or agency has broad flexibility of use. Sadly, this is flawed thinking.

When discussing commercial catalogue music, the brand or agency haven’t bought out the rights, they’ve just purchased a licence which will be limited by term, territory, media and context of use.

I recommend you don’t use the term “buy-out”. Instead, refer to a “licence”.

In summary:

- “Term” is the length of licence period

- Short terms are disproportionately expensive

- “Territory” covers the markets in which the campaign runs

- The larger the Territory, the higher the fees, especially if it includes USA “Media” covers the on and off line channels in which the campaign runs Online media is increasingly priced like broadcast media

- Context of use is also an important cost driver

- The more overt the branding, the higher the licence fee

This blog is an excerpt from my book Music Rights Without Fights, to get your copy click on this link.